Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and a simple knowledge model. #Health

The 3 Es: employment, ‘ealth and education

Photo by Milad Fakurian on Unsplash

The previous post presented a knowledge-distance view of care but what does knowledge itself look like in health? Here we build a model of information in health and discover how to connect the information we can access with the people whom we need to help us: the interactive-interpersonal model.

Let’s focus on professionals within the NHS: doctors, nurses, physios, and so forth (although the model also works for patients and carers). I’ve worked on this model for ~25 years, the most recent version being Young and Klein (2020), with background in Avison and Young (2007) and Connell and Young (2007). At the centre is the information seeker who needs specific knowledge to make the next decision – i.e. anyone in healthcare!

Information sources include books, journals, on-line repositories and databases, including medical records. Equipment can also produce information. Of special interest are imaging – X-rays, ultrasound, CT, MR – and clinical laboratory that analyses bodily samples. Both have mushroomed in the past century but for us they are black boxes: someone or something goes in, and a piece of information comes out, a radiologist’s report, a test result, perhaps a diagnosis.

This knowledge terrain has entranced health strategists since the eighties. It resembles the enterprise resource planning systems used in manufacturing or retail. Not surprisingly, planners have believed that if healthcare could get its act together, digitise its data and share it around, everything would be fine. Several attempts have been made to do this, the largest being the National Programme for IT in the noughties.

Why have they failed? First, almost all their thinking has focused on the top half of our model, which is only half the story. Health is different from other sectors because so much is in the people. The in-person knowledge matters critically, along with the conversations, and other agreements that generate and surface it. So, we draw a line between the interactive and the interpersonal.

However, there isn’t the infrastructure to support the interpersonal dimension properly – anywhere the world. No amount of investment in the top half of the chart can compensate for a lack of capability below it or provide sufficient support for decisions that rely on judgement, experience, or compassion.

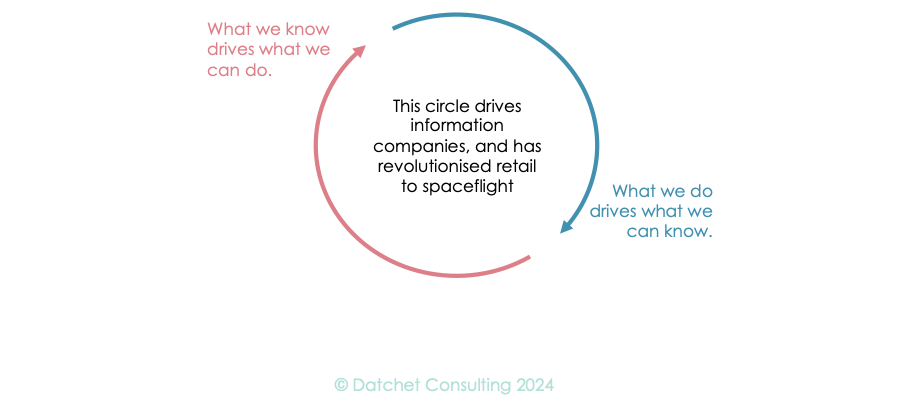

A second reason is that knowledge is sterile on its own. The dynamic that drove a home shopping boom under lockdown (while healthcare languished) was the virtuous vortex that knowledge drives what you can do, which in turn drives what you can know. However, care delivery organisations use very little of their information to drive process, and their services tend to yield limited operational knowledge.

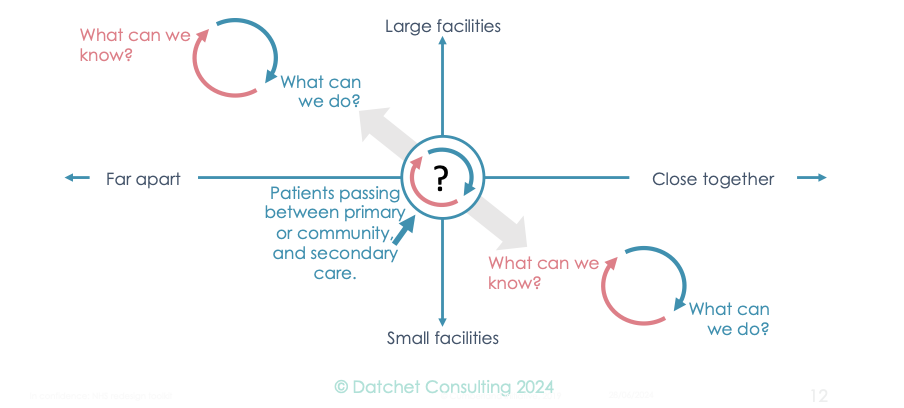

We can combine our models for a fresh view of the 7½ million who are waiting, by returning to our knowledge-distance paradox. Since the main flow of patients involves the top left and bottom right, we have created a portal for the flow of patients between them, which gives us three regions in which to apply our virtuous vortex by asking ourselves, in each case, what we can know and what we can do.

That is why the best approaches are hybrids and why any successful initiative on waiting must extend beyond the top left or bottom right. We note that there are three main options, namely:

Extend capability in primary and community care to include some hospital activity. Thus, Darzi polyclinics, essentially souped-up GP practices, with imaging and better diagnostics along, perhaps with minor surgery, would spare many patients a trip to hospital, while hospitals would benefit from lighter loading.

Extend the reach of hospitals into the community. There are already hospitals that have taken over GP practices to create vertical integration. This is essentially the inverse of (i) above.

Create new community-based services with some capabilities of hospitals. There has been lots of experimenting with one-stop clinics, and more recently with Community Diagnostic Centres, CDC’s.

This model shows why health is different from other sectors. Like other sectors, there is domain knowledge to be mastered: how bodies and minds function, how drugs work, etc. There is historic knowledge, such as medical histories. Increasingly, logistics information knows where people and things are. You can look all this up in a well-run information system.

However, there is interpersonal information, too: experience, memories and judgment. This may surface in many ways, in a corridor encounter, perhaps, or at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. I’m told the latter are good in complicated cases; as a patient, I’ve found they’ve usually been dominated by the most senior person.

Thus, the health information seekers’ circle of knowledge has an interactive half that looks like other sectors and an interpersonal half that doesn’t. Critically, both red and blue triangles must connect to appropriate knowledge sources if the HIS is to progress with their day.

As a patient, my journey has been more varied: the consultant is just one of the interpersonal and interactive networks. I’m an extreme case, but to give an example of how eclectic and disconnected these encounters can be: the NHS no longer provides under-arm crutches. I need leather stirrups below the handgrips to hang onto the crutches, so I recently picked up a set of six stirrups from a local saddler as part of my mobility mission!

Evaluating your information system.

The trick is to sit in the seat of each person along a patient’s journey or member of staff’s day. Use the diagram of all possible knowledge sources (or produce your own version of the diagram with your sources) as a guide and keep asking yourself:

(a) What information is needed to proceed?

(b) How easily does the system enable that information be accessed?

If access is slow – repeated logging in, for example – don’t tick that box. If you must infer an answer by asking a slightly different question, that information is out of reach. Note, many workarounds are extreme: a primary care nurse may discover that an elderly patient did not attend an appointment because the latest clinical lab tests were ordered from a ward – so the patient is in hospital.

In a formal assessment, you work stepwise through whatever pathway you are following and tick the box each time you can answer the specific question:

Can the right person get the right data in the right form in <20 seconds?

At the end of the process, you’ll have a much clearer idea of whatever information capability you have, or indeed what the vendor’s sales team is selling you, than many hours of seminars or presentations.

Even with all the interactive and interpersonal connections, most patient pathways are too complicated to map out by hand, especially with millions of encounters a day, so we must turn to the challenge of managing such complexity. Next!

Professor Young: researching for 40+ years; in healthcare for 25; and using NHS limbs for 50+.