Photo by Cash Macanaya on Unsplash

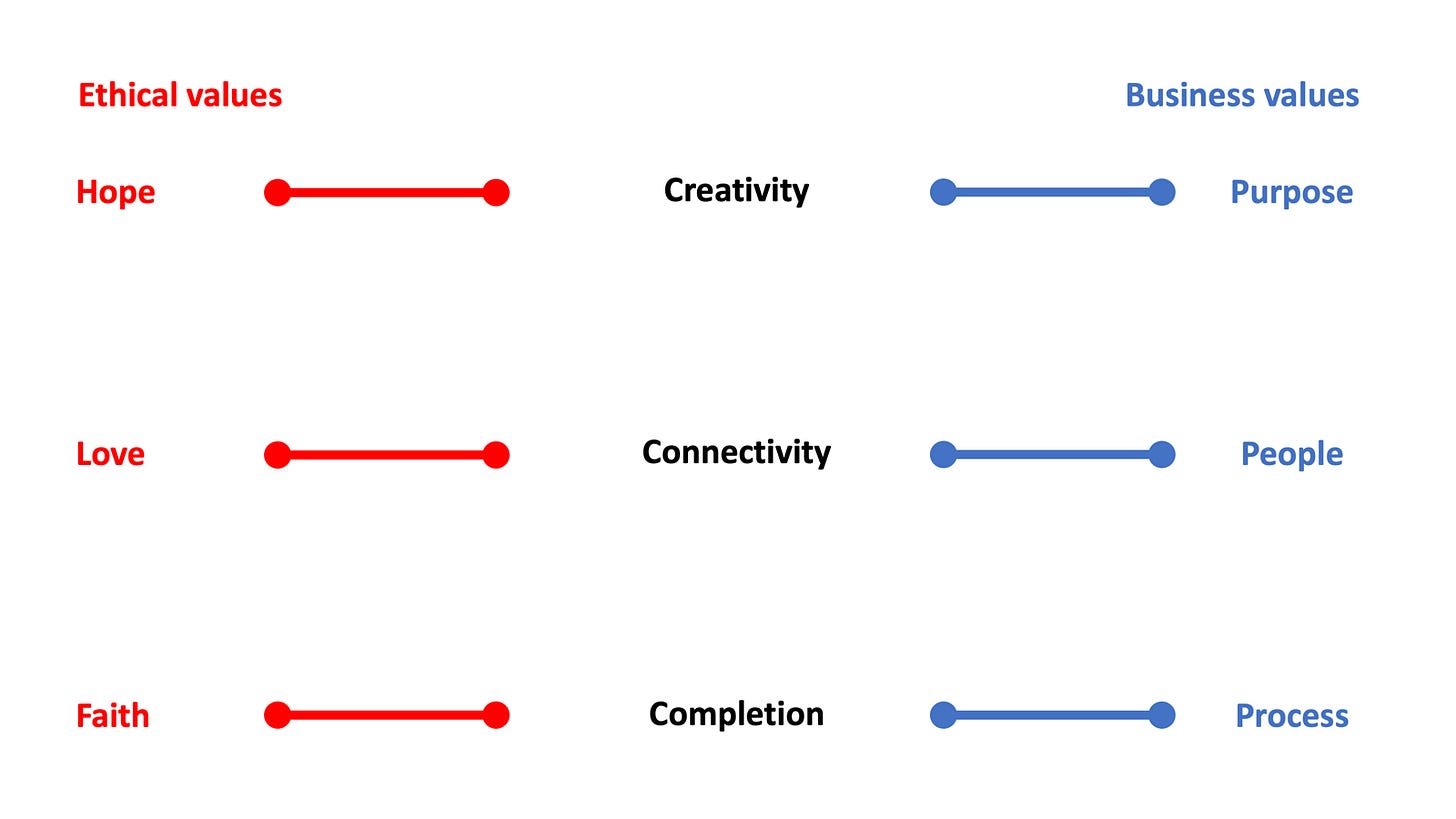

Our previous post (see here) on creativity and connectivity energy, used the lens of hope, love and faith, mapped across to the common elements of business excellence – purpose, people and process – to make the link between Christan virtues and business excellence (our original framework is here).

Having looked (link) at what makes the workplace toxic we now counterbalance it with some sense of how the workplace also brings re-energising and exciting experiences.

At the heart of our kingdom lens, we see this energising going on in three ways: creative energy, connectivity energy and completion energy. For completion energy, we use experiences from Japanese manufacturing in the late 20th century.

We each found ourselves visiting Japan: Terry’s 1989 research lab visits are described here, while Phil’s missions in the 1990s led to a series of IET papers, A state of discontinuous improvement (here), Removing the oily rag (here), Total Differentiation (here), and Asia as part of Japan (here).

Phil accompanied groups of businesspeople to explore factories that were pursuing the Total Production Management accreditation. On the face of it, this had no possible connection with any Christian lens on work or business. Yet it was on these visits that he found many examples of completion energy – on the bottom line of our framework, connecting faith to process with a perfect outcome every time.

In industrial terms, of course, this is very much Japanese territory. On one of his visits, a leading Japanese professor of manufacturing engineering asked Phil if he really understood Kaizen. Phil explained that he understood it to be a systematic and continuous process of very small changes that keep the product or process in a constant state of improvement. Using Formula 1 cars as an example, he noted that tiny improvements, consistently applied had made huge difference to performance.

The professor politely suggested that Phil might have missed the point. He showed him how every group in the plant documented (mostly with pictures) their successful improvements and a one-page copy was shared with every other department. Each area had a huge collection of these one-pagers housed in what looked like wallpaper selection catalogues.

Most of the ideas didn’t translate directly to another area. What did translate was the thinking and methods so that improvements from one area triggered fresh ideas and experiments for another. The point was that Kaizen was not just about continuous improvement, it was about shared improvement.

Every employee had the opportunity and encouragement to be creative, to try things out and to enjoy the tangible results of their efforts. Everyone could enjoy the workplace magic. At the time of Phil’s Japanese factory visits, it wasn’t unusual for UK businesses to have suggestions schemes, but rarely did they ever create any sort of energy and hardly ever did the ideas ever get implemented.

The philosophical, almost religious, roots of Japanese process design in manufacturing stand out if, for instance, you compare Taiichi Ohno, who died in 1990, with western writers who expounded his thinking. His Toyota Production System (in translation, here), is essentially about how to think about manufacturing, while Womack and Jones’ Lean Thinking (first published in 1996, read here) has gone a long way to sharing the practices, largely in terms of guidelines.

The outcomes of shared Kaizen ideas typically simplify products and processes and thus reduce the cost and time of manufacturing and improve the quality. An important biproduct is often an improvement of the employee experience, less stress, fewer mistakes, less risk, greater comfort, less fatigue, improved sense of achievement. These are important ways to restore and redeem the workplace, and worthy goals in their own right.

It is easy to walk round Japanese plants without acknowledging the worship spaces in every site. In the same way we might not recognise that in Malaysian factories time for regular prayer must be factored into the shop floor economics.

Meanwhile, Christians sense a yearning for glory, heart and perfection.

Let’s leave the last word with the Preacher (Ecclesiastes 3:9-12, NIV):

What do workers gain from their toil? I have seen the burden God has laid on the human race. He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart; yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end. I know that there is nothing better for people than to be happy and to do good while they live.