Fixing the NHS: making the virtuous vortex work. #Health

The 3 Es: employment, ‘ealth and education

Photo by Onur Binay on Unsplash

This series is about hoovering up millions of waiting patients and whisking them to successful outcomes. Most need a diagnosis, after which some need surgery, medication or therapy, or they may need to learn to manage their condition. Some just need time to decide what they want to do next.

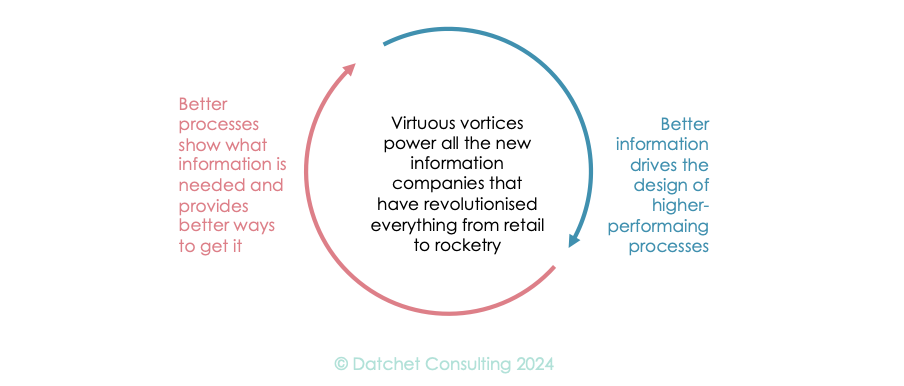

This magical hoover must tap into the virtuous vortex we have already presented, where information feeds process that generates information... However, the NHS has tried several radical overhauls since it was born, so we must look seriously and honestly at the past.

We want a service that does better by learning to do better still.

Virtuous vortices

Within our centres, the virtuous vortex relies on data-informed processes that know how long everything takes – max, min, median – how long patients and staff wait, and how to deliver the same high-quality experience every time. In turn, these processes must feed real-time information back into the system. We don’t want staff to waste time hunting for resources, so the next free room, scanner, or diagnostic test area must signal its readiness before it becomes free for use. That way, the right combination of patients, staff and equipment may converge smoothly to the right place at the right time, every time.

The system must also measure busy-ness, allowing staff to work at their best, getting their breaks with a mix of activity that enhances performance. At this point, Lean purists might mutter about takt time – a way assembly lines are synchronised to the beat of demand – but that’s not what I’m proposing. This isn’t a single line – it’s a dance through knowledge-reliant encounters in an environment of very expensive equipment. The choreography of care, therefore, matters as much as clinical outcomes (which matter absolutely).

If this sounds like a nightmare, then you’re planning to sweat your staff and assets to achieve your targets. Walk away, now!

Your centres are part of a wider system that they draw on, particularly in identifying the right patients and in getting them ready for this high-impact encounter. If patients need blood tests or a good medical history on arrival, make sure these are completed the day or week before.

Feeding out from the centre, what is discovered there must make its way back into medical records and clinical notes. The broader learning can also be fed into the wider system to smooth patient flows through GP surgeries or hospital wards and outpatient departments. How these waves of improvement – knowledge and process – percolate through the wider system will determine whether you have created lifeboats to save the NHS or toxic bubbles that kill any service they bump into.

Why has the NHS been unable to sustain a virtuous vortex in the past?

This question disturbs anyone in health service research and has puzzled me (e.g.: Avison & Young, 2007; Connell & Young, 2007, McGrath et al, 2008 and Young and McClean, 2008). Here’s my angle from an information perspective:

The NHS rarely achieves a positive, real-time, connection between its performance and its knowledge base.

This is going to be awkward: my analysis won’t be popular and a core idea comes clothed in a cultural allusion that is difficult and contested today. However, I don’t know how to deliver the idea naked, so let’s start with Richard Feynman, the Nobel Laureate, and his Commencement Address at Caltech in 1975. His Cargo Cult speech warned of practices in science using a sustained metaphor of how we often do things that look right without getting the science right.

I’ll leave you to read the piece for yourself. If you’re into healthcare, it’s much more important that you read it than the rest of this post. Done? OK, here are some cargo cult NHS projects – right words and imagery, missing mechanisms. We’ll start with two that looked spot on, and yet failed.

(a) The Modernisation Agency in the nineties. In a sense, this was half of the right idea: the process side of the process-knowledge vortex. However, they tried for an information-lite approach, beguiled by a mythology of elegant self-replenishing processes and buckets of whatever, making the rounds.

Lean works on a shared concept of value to the customer where healthcare has dozens, maybe hundreds, of unconnected measures (see Young and McClean, 2008) and while the lingo was Lean and Theory of Constraints, the implementation was ‘cookie cutter’ methods. These methods were already simplified versions of a westernised take on a philosophical, almost religious, idea (see Taiichi Ohno’s Toyota Production System).

It took industry decades to get Lean right. A Technical Director at BAE Systems, for instance, once told me that the most valuable gain from its ownership of the Rover Group (‘88-‘94) was the transfusion of Lean into its own manufacturing. And don’t forget about Honda’s partnership with Rover in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Lean was hard and took a long time.

However, before the Modernisation Agency could get on top of Lean, things had moved on.

(b) The National Programme for IT (NPfIT), later Connecting for Health (CfW), in the noughties. Next, the NHS set about the other half of the vortex, but without a coordinated effort to redesign processes. Apart from questions over who should access what, there were only hand-waving ideas of how it would work despite amazingly robust contractual arrangements to deliver the infrastructure. Without solid mechanisms to turn this knowledge into enhanced care for patients and higher levels of performance for the NHS, it could never succeed.

By the mid ‘90s, Walmart was completing a decade-long series of landmark satellite link, network and internet, projects and had spent (with its suppliers) roughly similar sums (see a roadmap here). However, Walmart’s big idea worked because it knew exactly how to transform knowledge into faster service and better performance (and, of course, profit). It already had the point of sales technology in place from the ‘80s and knew why every hour saved in a product’s journey to the customer was worth it. It knew how much local decision-making was worth and the value of the centre having a real-time global view of the business. For the NHS connected information was a field of dreams.

When I moved house in this decade, I had to have my X-rays and CT scans taken again for the local digital repository. The field of dreams is still a little empty.

We could go on: the 4-hour wait, Vanguards, and Integrated Care Systems. Each had an admirable aim, and for me each has fallen prey to the cargo cult of copying a great look but failing to put critical mechanisms in place.

In an industrial context, Hill and Wilkinson (Employee Relat. 1995, 17, pp 8–25.) noted:

“the original ‘gurus’ of quality management have been long on prescription but shorter on analysis and, moreover, have differed among themselves.”

In industry, companies went bust or found a survival path amid this chaos and the survivors learned what really worked. The NHS wasn’t given that chance or been allowed the dubious taste of that risk.

If our centres are going to work, they will need robust internal mechanisms and viable combinations of knowledge and process, as well as outward conformity to best practice, while remaining stable for at least a decade. That’s a tough gig.

Professor Young: researching for 40+ years; in healthcare for 25; and using NHS limbs for 50+.

The series

Fixing the NHS: hurdling todays barriers for a fitter future (25 July 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and a simple knowledge model (1 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and service design (8 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and getting the right numbers (15 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: making the virtuous vortex work (22 August 2024)

How to design a centre that closes 4,000 patient journeys a month for £1,000/patient or less, all in (29 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the bite-sized story in 6 charts (5 September 2024)