Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and service design. #Health

The 3 Es: employment, ‘ealth and education

Photo by William Rudolph on Unsplash

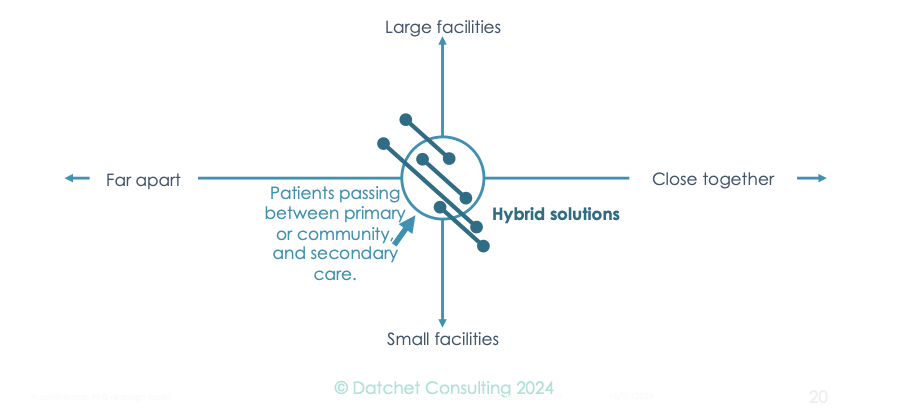

Clearing backlogs needs hybrids that bridge top left and bottom right quadrants of our care delivery chart. They must swallow up patients quicker and more cheaply than we can now and with better outcomes: a cure, or a long-term management plan. How can we do this affordably, reliably and fast? To find out, we’ll look back a century and see how strategists tackled the hybrid problem of creating airports at sea.

Are we talking about mini-hospitals or super-clinics? A comparator was the aircraft carrier: part ship, part airstrip. After years of wargaming, developing doctrine, and shaking career ladders it became the principal projector of military power – see Rosen’s Winning the next war.

A sea change like this is needed to transform healthcare but it will confound our intuition, since applying our experience from similar situations is often misleading. For instance, in the early days when fighters attacked the Ark Royal’s, its own fighters were kept below deck so as to clear the gunners’ field of view.

While the Royal Navy regarded carriers as ships, in 1923 the US Naval War College at Newport RI played map-and-dice war games with more carriers than existed in the world at the time. The results were astonishing, provided you could pack carriers with aircraft, fly them for a few hundred miles and land again at sea. This was a crazy dream, yet hulls laid down in consequence changed the balance of power in the Pacific 20 years later.

To develop a hybrid service, just follow suit, with computers instead of dice, to address two questions:

i. What design works best?

ii. How and when might this design fail and how does one recover?

Although Kaiser Permanente mock-up services at the Garfield Innovation Center, the UK tends to build variants of what it – or someone else – has built in the past, but with improvements.

We need designable services rather than refinable services.

Is anyone doing it right?

The hiatus of lockdown enabled BADGER (Birmingham and District GP Emergency Room) to develop drive-through, socially distanced, clinics (see Agile care in a time of lockdown, Health Estate Journal, 2022; How to design and build a care system: from jargon to achievement, Chamber UK, 2022). It was fast, cost-effective and patient-focused:

The primary care collaborative that built it was miniscule next to a hospital

The drive-through clinic served its first patients within months

Repetition and redesign produced a bespoke city-centre unit within two years

It delivered patient-booked services without waiting

Workforce renewal

Back in the ‘20s, naval aviation faced two challenges: training pilots and navigators for the navy; and ensuring that trained staff reached positions sufficiently senior to make an impact on strategy.

In the UK, they had to switch from the RN to the RAF to train and then move back afterwards. Neither service trusted its rival so almost no pilots or navigators influenced policy, unloved in training and tainted thereafter. In the US, Rear Admiral William Moffett, first chief of the US Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics (founded, 1921) fought for pilots and navigators ensuring their promotion to senior ranks where they wrote naval doctrine. With heroic leadership, he built something new from the ground up.

In health, too, there are challenges in training a new workforce and then ensuring key members are promoted to a level where they can impact strategy.

To disconnect the discussion from such issues, I think of all healthcare staff for rapid access services in terms of 4 functions:

Decision-maker and interpreter. Diagnosis and treatment options require choice to be made. Doctors are trained to do this, so most D&I staff will be medics, although others today can prescribe and diagnose.

Clinical Technician. This is someone who operates a piece of equipment, performs a surgical intervention, or intervenes in other ways, and may include many types of healthcare worker.

Process specialist or manager. These will often be closest to the patient and run their care. Clearly, nurses and HCAs will be the mainstay, but their differentiating skills will be to keep processes on track.

Flow manager. Such staff smooth the way for patients (and staff) to move through the system. A good receptionist might be a flow manager, or an HCA who escorts a patient and perhaps helps them with changing or onto and off a scanner, intervening as needed so that everything ticks along.

A starter for 10

You’ll need an experienced facilitator to assemble all stakeholders, elicit the skills and training needed and to ensure the plans for the new hybrid use just these building blocks. This model need not be precise but must track time and resources. Rough costs will do but if you use official unit costs your overheads may be inflated by the dysfunction of whatever you are replacing, so be careful.

Iterate and refine

Encourage the team to experiment with a focus on patients: what they will experience, who will ensure they go where they’re needed next, how long decisions will take, whether you run appointments or walk-in access, etc. You’ll probably find you need lots more flow managers than expected.

Once you are sure you can reliably close patient pathways for £1,000/patient or less, move on to load testing – what happens when staff fall ill or demand surges. Then turn to metrics and assess them under different conditions.

Finally, make the model available in a form that is easy for anyone to play with – including patients – and that will run from any computer. Give anyone who wants it a chance to experiment and comment.

Once the complaints and suggestions tail off, you’re good to go!

Is it worth it?

I’ve worked with others for more than 20 years to the estimate costs and benefits of this design approach.

This is early work with many assumptions – but it looks like every £1 spent on robust digital design yields >£30 later in savings or enhanced performance. It was hard to find returns below 10, while some examples topped £1,000.

Here are some of our findings:

Can you afford formal digital design? The real question is can you afford to go without it?

Professor Young: researching for 40 years; in healthcare for 25; and using NHS limbs for more than 50.

The series

The series

Fixing the NHS: hurdling todays barriers for a fitter future (25 July 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and a simple knowledge model (1 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and service design (8 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the digital arts and getting the right numbers (15 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: making the virtuous vortex work (22 August 2024)

How to design a centre that closes 4,000 patient journeys a month for £1,000/patient or less, all in (29 August 2024)

Fixing the NHS: the bite-sized story in 6 charts (5 September 2024)