The Dark Matter of creating time in health management

Chapter 2. Dark Matter: vital, invisible, management skills

Photo by Aron Visuals on Unsplash

Chapter 2 in our series of posts from Dark Matter.

The short read.

Using the model from chapter 1, we now focus on the other two quadrants: investing and offloading.

Investment spends a fraction of our time to reap a benefit in terms of multiples of our time.

Offloading involves handing things on to others as well as simply cutting things out of our lives. In stepping into management, some things we hand over and therefore stop doing are often those things we have done well up to that point.

We note how the benefits of investing are generally reaped by the gains of good support, teams and administration, to which we offload activity.

Investment may involve learning enough to be able to improve the system or develop more effective teams…

… which usually means investing in developing our own skills.

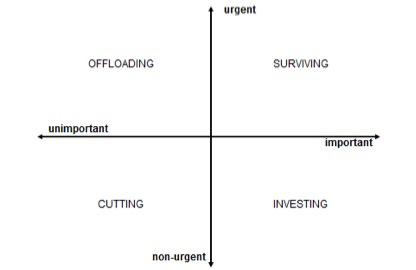

Figure 1.1 (from chapter 1) - a framework for discussion: importance and urgency

Two or three hundred years ago, the entire time management agenda, inasmuch as it would have been conceived of at all, would have focused on the top right and bottom left quadrants – on surviving and cutting. As a lone healthcare worker – perhaps the village midwife or local doctor – you would have cared for your charges, looked after the billing, decided who deserved charity and how much, ordered what you needed, and supervised directly any assistance you were able to hire or press into service. And, of course, the transport systems of the day would have restricted your served community in a way that probably helped you to survive. We will leave the question hanging as to whether conscious cutting would have featured in your thinking or whether the non-urgent and unimportant would simply have drifted out of your life.

Today, by almost any outcome measure, healthcare workers achieve many times more than their eighteenth-century predecessors. To multiply yourself several times over involves more than squeezing more out of a busy week. So, what has happened?

Well, lots of things. Florence Nightingale harnessed the power of statistics to guide care delivery, while a century later a group of industrial innovators – Deming, Shewhart, Ohno and others – used the same magic of numbers to streamline the business of getting things done, and in the process contributed to rebuilding Japan’s industrial base of after World War II. Drugs, diagnostics and technology have transformed the scene beyond all recognition and serve as massive force multipliers in diagnosis and treatment.

Meanwhile you need not worry about collecting money from your charges. Somebody else charges. You need not chase debtors, either, since someone somewhere takes a fraction of a penny from most working adults in the country and pops it into your account at the end of every month, freeing you from the disconcerting tasks of working out whom to charge and then chasing them up. Materials are ordered, hospitals are built, social systems kick in, and generally, you are free to practice. Even if you are a self-employed GP, a lot of the financial mechanism is managed by others.

If the secret to making a little more of yourself lies in the surviving and cutting quadrants of figure 1.1, then the secret of multiplying yourself several times over lies in the other two. And there is usually an interplay between them.

Time creating strategies

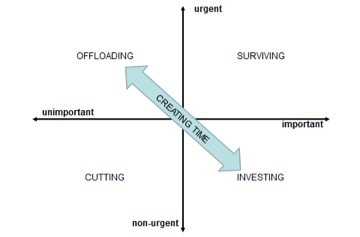

Figure 2.1 – Our time management framework: creating time

Investing:

This quadrant is all about the long-term view, which means there is probably no immediate pay-off when you get a decision right. People are rarely praised just because everything goes smoothly. Top class management is almost invisible – as our title says – and so this is the most unfair quadrant of all, demanding time and attention with the guarantee that, if you get it right, almost no-one will notice.

Actually, it is not quite as bleak as that, since many metrics can only be met by a well-oiled machine that delivers consistently and without adrenaline. And slowly, metrics are winning the day.

Slowly, too, the business of strategic planning is being recognised and increasingly there is time, if not budget, for management training, away days and the like. The difficulty lies in prioritising the follow-up and putting the personal planning time into otherwise busy days. Investment is always difficult. Even in business, where so much is quantifiable, the best managers stand apart from the rest in being able to allocate prime time and effort to the intangibles that the accountants cannot see, and the customers do not want to hear about. Only you know what those intangibles might be. Their importance may not yet be fully clear to you, but your job is to make sure they get enough of your attention – high quality, thoughtful, interactive, airtime – to ensure the future success of you and your teams.

Perhaps the hardest thing to allocate time for is reflection, either on your own or with others. Something that works for me is to listen to management speakers. It is not so much that I learn new things (although I generally do) as that I get time to bring the problems of the day to whatever standards or measures they are presenting. I find that a lot of critical details in everyday problems are well-nigh invisible from close up, and the chance to get away and think about something else, gives me that broader perspective. Travel to conferences can do that, too.

Every successful manager has a way of scheduling in the long-term view on a personal basis and also for the team. The challenge for each of us is to find the ways that work best for us. For instance, some people find it useful to have a professional coach, whom they meet regularly and with whom they can work through the challenges of their role. Increasingly, companies are prepared to pay for such support.

Because investing and offloading are so closely connected, we need to consider the worlds of bureaucracy and administration before we can make real sense of bringing the two together.

Offloading

Most systems have been put together in order, at least in principle, to take the burden from most staff. The difficulty is that so often the burden returns and builds up. You cannot read every detail of each expense claim or check every item on every case for support. But, for better or for worse, the buck stops with you, and you have to sign it all off.

I am all for challenging the system, and when you do you will discover a lot of process that no longer makes sense. If you can, consign it to the ‘offloading’ quadrant as soon as possible, not just for yourself, but for everyone. However, after eliminating the unneeded, there will still be a lot of signing-off to be done. In my view, there are three ways of handling this workload: develop more of a system to take it on (investing in offloading below); learn short-cuts that give you the basics; or develop a high level of trust with your team so that your sign-off is more-or-less automatic.

Finding your way around the paperwork and establishing your own set of checks and balances can work. Deep dive every now and again to make sure the numbers add up; pick out some cases and subject them to scrutiny to keep the process honest; but the aim is to learn what you can take at face value and sign it off quickly. There is a mantra that you cannot be too careful when spending public money. The truth is that you certainly can. You can spend so much time making sure that there is no failure in any aspect of a bureaucracy, that you have no time for anything else. Life is full of risks and managing risk is a management task. Take reasonable measures to check things out. Keep concise records (perhaps with a brief e-mail at the time of critical decisions); but use your judgement.

And now, for the matter of trust. There are those, particularly in senior positions in the private sector, who seem to get by entirely on trust. Some do not read anything; they consult and if their team says it is fine, they sign. Establishing such rapport with the team takes time. It may require a piece of savagery on an early expenses claim to make clear what is and is not acceptable. It may mean rapid dismissal of those who lie, deceive or pass the buck. It may be that you cannot make the trust criterion stick. Maybe you lack the authority, or do not like confrontation, or you are incapable of developing that type of relationship. If so, you must find another way to work. An obvious strategy is to team up with someone who complements you and is able to take on this part of the role for you. In the best cases it can work for everyone.

But somehow, you have to find a way of keeping the bureaucracy at bay.

Investing in offloading

If the systems exist, the first thing is to use them. When I first moved into the academic world, I was used to close administrative and secretarial support and set about trying to get myself a PA. Everyone told me that I did not need a PA, because the general factotum of the academic world was the Research Assistant, or RA. In the end I got what I wanted but it took me nearly a year. I still think the time to get a PA was a reasonable investment and so I made the case that other professors should have such support. Several years later, closer support was allocated but most professors still kept their own diaries and kept their PAs in the dark. In the end, the system reverted back to the old system for everyone else (I did a special deal on the back of a very large grant). If the supporters are there, learn to use them before you lose them!

Which is where the investment comes in. How much time will it take to reap the benefits of the system, by learning to work with one of the most important gateways to it?

The trouble is, of course, that many bureaucracies have grown to such a size and scale that they become self-serving and, even where there is no intent to focus inwards, the complexity is such that perverse and conflicting outcomes frequently occur. Rules, often set up to prevent some element of harm, impede critical activity.

The investment decision here is when to find a work-around and when to wade in and change the system. The difficulty is that new, and often poorly thought-out, procedures are introduced so often that you could spend your whole life resisting the tide of inane initiatives. This makes another connection between investing and offloading: what fraction of my time do I need to invest in administration and other things to get enough of a time-multiplier in the end? And, although you may not have articulated the problem in this way, you have probably already reached several pragmatic balances.

But what about investing in yourself to invest in the system? Is it worth studying for that MBA, or a Masters in IT, or learning about systems thinking through a course of reading? Do you lack the skills to talk confidently about process to propose new ways of doing things that will save many people a slice of their working lives?

This opens up deep questions. For instance, how much longer do you hope to work and what sort of impact you would like to make in the end? How much of your life do you wish to spend in close, interpersonal, hands-on, care, and how willing are you to mediate your skills and expertise through others?

Systems, particularly systems of people, are fiendishly complicated and full of confounding behaviour. It can take longer to develop a good systems engineer than it takes to make a consultant. But all is not doom and gloom. You need not be an orthopaedic surgeon to know the value of an X-ray in diagnosing a broken bone. The same is true in the world of streamlining bureaucracy and multiplying your efforts through the long arm of better processes.

Eli Goldratt (The Goal) has probably gone further than anyone else with his Theory of Constraints to distil a simplicity from the business of running a factory (or anything else) and offering a simple set of tools about which bit of the system to tackle in search of improvement. The NHS also has a lot of helpful material – guides to Plan Do Study Act and so forth – to get you started without too much investment.

Although Nightingale had a century's head start over Deming and his peers, it is still sad that health workers remain much better at delivering rather than designing robust healthcare delivery systems and services. It’s probably because she wasn’t a doctor and rather distrusted doctors (who cordially returned the sentiment), but the challenge for the present generation is to dive in and change all that.

And some are. As an external examiner, I get to chat to medical school students who have taken a year out to do a business qualification. They are ferociously bright, frighteningly hard working and do more in their undergraduate year than many MBA students. One year I felt there was a difference in the cohort. They were switched onto customer focus and what it meant for patients. They understood branding and had more information systems theory under their belt than I do. But something was missing. I asked one of them why there was so little emphasis in any of their projects upon management as management – the business of coordinating resources and making things happen, of planning, logistics, and making the whole system flow. Ah! She told me that administration could be left to the clerks and practice managers.

I don’t want to turn off a large chunk of my audience, but GP practices depend much more for their smooth running on the nurses, the practice manager, and especially the booking system operated by the receptionists, than on the doctors. The doctors do something that nobody else can do, but practice managing the flows and undertaking the associated activity is usually being driven by others. My take is we all suffer because doctors aren’t more involved.

Jan Filochowski (Too good to fail?), who was Chief Executive of several NHS hospital Trusts, spent a year at Harvard and got into Lean Thinking. That was his investment. On his return, he started to lean out an orthopaedic waiting list and discovered something surprising. The people whom he needed to convince, for whom he needed to find the right graphics and statistical presentation, were the medical secretaries: it took time to find the critical managers of the waiting lists.

My belief is that better management practice and service design are the untapped keys to better, more equal, and more responsive care in the decades ahead.

Investing in systems of people

While we will move on to talk about teams in the next chapter, the critical element here is that teams take time, and this investment is at two levels. First, there may be your own investment to pick up the skills to enable those around you to multiply their skills and yours to greatest effect. So, you may want to invest in skills: how do you handle the difficult team member? There are ways to get the most out of each person, but at what personal cost? Is there an ideal structure for your team?

The second level is that teams themselves take time to gel. Tuckman's famous model of team evolution considers four main stages: forming, storming, norming and performing – perhaps with mourning or adjourning as further stages (Wikipedia is a good way in).

My research involves leading large research teams from several universities. The teams have included doctors, nurses, statisticians, ergonomists, bioengineers, social scientists, information systems specialists, modellers, and good old-fashioned engineers. And I have realised that Tuckman was right. It takes time for teams to gel. There are times when the friction is palpable and it has to be that way – without the early friction there is no polish later on. But teams do come to feel comfortable with themselves, in time. Some of the signs caught me by surprise, as when a couple of the Research Fellows suggested a Secret Santa one Christmas. With a cap of £5 per present, a lot of unofficial teamwork went into some of those presents. I can think of a T-shirt sporting the project logo and a picture of two of the staff lounging in a hot tub at some US conference. In real terms it was probably the most expensive T-shirt given away that Christmas – anywhere! But that cost was dwarfed by the value of such teamwork to the project.

Sometimes the teamwork will have you as the butt of the joke. I remember going to a partner university, only to encounter my face on the notice board with a message below it (and I quote from memory) ‘You work 8 hours a day for me, and the rest of the time for yourself.’ At other times it is really touching. When one chap left, they sent me a photo of the cake they had ordered for the goodbye party. And to my utter amazement, there was my face staring out of the icing. Teams will turn your ideas into gold. But they are fragile, and they take time. That is your investment.

You may also want to invest in relationships. The lunches getting to know people, trying to find out what matters to them, and whether your vision can work alongside theirs. The time to work out how people like to be influenced: does a given director like a chat in the corridor, a 1-page summary, the original report in all its glory, or some pictures, slides, or whatever?

In a nutshell

So the job needs three of you. How do you manage?

We have shifted our focus from saving time (surviving, cutting) to creating time through investing and offloading, where the trick is to work out what you can invest as a fraction of your time, to gain a return in terms of multiples of your time. And this benefit will normally come back to you through the top left quadrant – offloading to the administration and bureaucracy!

Whether this means a little more reading or a major programme of education and training is the key question for you. But here are some ideas for structuring the problem: sort out where you stand on the administration and the extent to which you will live with it or seek to modify it. Advancing on this, learn more about systems and how they work and how you can improve services within reason. And finally start to decide how much of the team working and interpersonal agendas you need to manage, and set about acquiring the critical skills.

For reflection

1. Choose a selection of people around you (include some to whom you may report. Ask each of them what they think you ambition and intent is. How well do their response align to your view?

2. What are the most significant investments (in any currency you choose) that you have ever made? How will you make a return on them?

3. Think of the worst bureaucracy you know. What are the three most important benefits that it offers, which you would not enjoy if it were not there?

4. Have you got a mentor? If not, how will you find one? If so, how are you using that resource?

5. Are you mentoring anyone else? If so, how? If not, why not?

6. What experience have you had of building a team - in any context - and what have you learned about the time it takes?

7. What is the best example of administration you have come across and why do you think it worked so well?

8. Plan your strategy for developing better teams and systems for the next 10 years. What is your investment schedule?

The story so far

Health Management: is there a problem? [Dark Matter introduction](30 January 2025)

The Dark Matter of saving time in health management [Dark Matter chapter 1] (6 February 2025)

The Dark Matter of creating time in health management [Dark Matter chapter 2] (13 February 2025)

The Dark Matter of small teams in healthcare [Dark Matter chapter 3] (20 February 2025)

The Dark Matter of team players in healthcare [Dark Matter chapter 4] (27 February 2025]

The Dark compulsions of counting in healthcare management [Dark Matter chapter 6] (6 March 2025)

The Dark Matter of simply managing in health [Dark Matter chapter 5] (13 March 2025)